We all know that discarded plastic bottles, cups, shopping bags, drinking straws, soda can rings and other items are harmful to the environment and marine ecosystems. That’s why thousands of New Jerseyans volunteer each year to clean up trash – much of it plastic – from river and stream banks and beaches.

We all know that discarded plastic bottles, cups, shopping bags, drinking straws, soda can rings and other items are harmful to the environment and marine ecosystems. That’s why thousands of New Jerseyans volunteer each year to clean up trash – much of it plastic – from river and stream banks and beaches.

But it’s not just the plastics you can see and pick up that are harmful. Microplastics – particles so small they’re nearly invisible – are emerging as a new contaminant of concern to marine wildlife and even human health.

Partnering with Rutgers, Baykeeper and others in regional studies

Local watershed watchdog Raritan Headwaters is currently investigating sources of microplastics in the upper Raritan River watershed as part of a larger network of organizations studying microplastics in the region including NY/NJ Baykeeper, Clean Ocean Action, 5 Gyres, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Raritan Valley Community College and Rutgers University.

During a pilot program last summer, Raritan Headwaters staff and interns sampled river water at 10 locations upstream and downstream of wastewater treatment plants along the South Branch of the Raritan River to measure the concentrations of microplastics. Fine mesh nets were left in the river for an hour at a time to collect solids in the water.

After the solids were sorted, organic materials like leaf and twig pieces removed, and the samples dried, RHA staff could count and categorize the plastics that remained. By calculating the volume of water flowing through the nets, they can determine the concentrations of microplastics in water at each location.

What are microplastics?

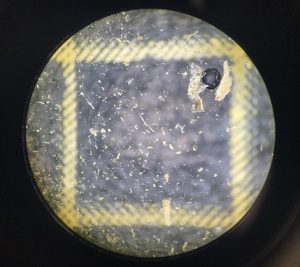

Microscopic sample showing black microbead (upper right corner). Yellow square is only 5mm wide.

Some microplastics come in the form of tiny beads found in personal care and cleaning products, such as face and body scrubs, some of which have been banned in New Jersey.

Others come from larger plastic items like bags and packaging breaking down into smaller pieces. And some are “micro-fibers,” or tiny strands of plastic, released by certain synthetic fabrics as they’re laundered. They range in size from 5 millimeters (the diameter of a pencil eraser) to microscopic scales not visible to the naked eye.

“Most of the really small particles of plastic don’t get filtered out by treatment plants,” explained Dr. Kristi MacDonald, director of science for Raritan Headwaters. A recent study reports that 8 million tons of plastic enter the world’s ocean each year, the majority of it in the form of microplastics.

Contaminants in the water like polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), pesticides and flame retardants can stick to microplastics, which are then ingested by fish and other aquatic creatures.

“When contaminated microplastics are mistaken for food resources by the species living within this habitat, they get incorporated into the food webs,” according to a NY/NJ Baykeeper study. “In fact, several studies have shown that microplastic contamination is found in the tissues of finfish and shellfish, which then has the potential to move up the food chain and pose harm to human populations.”

Dr. MacDonald and RHA Intern Kate Arnao are now in the process of analyzing the microplastics found last summer to determine their size and origin – whether they’re microbeads, microfibers or parts of plastic bags or cups. Dr. McDonald also wants to find out which sites in the Upper Raritan watershed have the highest concentrations of microplastics.

“We expect to see that the density of plastic particles goes up in the areas downstream from treatment plants,” she said, “By focusing our microplastic study on sites where RHA collects data, we are expanding our understanding of the health of our water both for people and for the creatures that live there. In addition, we hope to work with different stakeholders to address microplastic pollution at its sources.”

The sites where Raritan Headwaters collected microplastic samples last summer coincided with sites where Rutgers University professor Dr. Nicole Fahrenfeld and her students collected sediment samples as part of a study funded by a Sustainable Raritan Mini-grant.

How you can help

Residents in the North Branch and South Branch Raritan River watershed can help prevent microplastic pollution by:

- Participating in river and stream cleanups like the 28th Annual Raritan Headwaters Stream Cleanup on Saturday, April 14.

- Using personal care and household cleaning products that do not include plastic microbeads, many but not all of which are now banned at the state and federal level.

- Saying “no” to plastic bags, bottles, cups, drinking straws, eating utensils and other single use items.

- Choosing reusable items, like grocery bags, lunch bags, water bottles and utensils.

- Recycling plastic bottles and food containers properly.

- Buying clothing made of natural fibers.

- Taking action and staying informed by visiting www.5gyres.org, www.oceanconservancy.org/trash-free-seas and www.epa.gov/trash-free-waters .