Plastics are pervasive in our everyday lives. It’s nearly impossible to go even a day without using – and discarding – plastic items.

Plastics are pervasive in our everyday lives. It’s nearly impossible to go even a day without using – and discarding – plastic items.

Less than 10 percent of plastics are recycled, and many find their way into the environment, where they weather and eventually break down into smaller pieces. Microplastics – particles so small as to be nearly invisible – are emerging as a threat to aquatic life and human health.

A newly-released pilot study by watershed watchdog Raritan Headwaters Association (RHA) found that microplastics are present in the South Branch of the Raritan, a rural river known for its clean waters. The study was based on sampling at 10 sites along the South Branch.

“One thing that was very striking was that every single sample we took had microplastics in it,” said Dr. Kristi MacDonald, science director of the Bedminster-based nonprofit and author of the study.

The 10 sampling sites were located along a 23-mile stretch of the South Branch between Clinton and Branchburg. Four sites were just upstream of wastewater treatment plants and four were immediately downstream of those plants.

The main purpose of the study was to find out if wastewater treatment plants are a source of microplastics in river water. The study found that microplastic concentrations were indeed higher just downstream of three of the four wastewater treatment plants.

“It indicates that water users on the sewer line, including households, businesses, schools and others, may take individual measures to decrease microplastics in wastewater,” said Dr. MacDonald.

“The existence of point sources of microplastics at wastewater treatment plants provides an opportunity to target those places to minimize introduction of microplastics into the environment,” she added.

Health Concerns

Microplastics are created by either the breakdown of larger plastic items – such as water bottles, plastic bags, food wrappers and fishing line – or the manufacture of small beads added to facial scrubs, toothpastes and cleaning products. Microplastics also include fibers from clothing such as fleece.

Concern over microplastics is growing because of potential impacts on aquatic life and human health. Microplastics can be mistaken for food by small fish and other aquatic creatures, which in turn are eaten by larger creatures and become part of the food web. Microplastics can physically harm fish and invertebrates that ingest them, and they also can carry toxic chemicals absorbed from the environment.

Microplastics – especially microfibers – have been found in drinking water supplies, including tap water and bottled water.

Raritan Headwaters’ sampling of river water took place during the summer of 2017. Fine-mesh nets were left in the South Branch for an hour at each site to collect solids drifting downstream. The nets were then taken back to RHA’s laboratory in Bedminster, where the solids were rinsed, dried, sorted and classified.

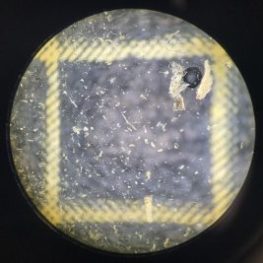

Microscopic sample showing black microbead (upper right corner). Yellow square is only 5mm wide

Once organic materials and larger solids were removed from the samples, RHA was left with about 4,000 microplastic bits measuring 2 millimeters – about the size of a poppy seed – or smaller. All were logged and photographed.

The overwhelming majority were “secondary” plastics, meaning they’re degraded fragments of bags, bottles, wrappers and other plastic objects rather than “primary” plastics like microbeads from scrubbing products or microfibers from fabrics.

Dr. MacDonald concluded that more study is needed to determine sources of microplastics in river water. Further study could also determine whether more microfibers and microbeads could have been found with even finer mesh nets.

“Plastics don’t go away, they just break down into smaller and smaller pieces,” Dr. MacDonald noted.

Reducing Plastics

According to Dr. MacDonald, the pervasiveness of secondary microplastics in the South Branch highlights the importance of Raritan Headwaters’ annual stream cleanup event, held each April. In 2018, cleanup volunteers removed 13.5 tons of trash from river and stream banks within the watershed, including 7,643 plastic bottles and 2,688 plastic bags.

“Our annual Stream Cleanup prevented those plastic bottles and bags from eventually becoming microplastics,” she said. This year, the Stream Cleanup is scheduled for Saturday, April 13; volunteers are needed. Click here for information.

The pilot study also highlights the need to reduce single-use plastic bags, one of the leading contributors to microplastics pollution. The New Jersey State Legislature is currently considering a bill banning single-use plastic shopping bags, as well as plastic straws and foam cups and containers.

This research was funded by Raritan Headwaters and through a grant from the Rutgers Raritan River Consortium. Co-grantee Dr. Nicole Fahrenfeld and her students at Rutgers University provided assistance with the processing of microplastic samples.

Read the microplastics study here.

About Raritan Headwaters

Raritan Headwaters has been working since 1959 to protect, preserve and improve water quality and other natural resources of the Raritan River headwaters region through efforts in science, education, advocacy, land preservation and stewardship. RHA’s 470-square-mile region provides clean drinking water to 300,000 residents of 38 municipalities in Somerset, Hunterdon and Morris counties and beyond to some 1.5 million homes and businesses in New Jersey’s densely populated urban areas.

Raritan Headwaters recently was accredited by the national Land Trust Accreditation Commission, meaning it has been recognized as a strong and effective organization committed to professional excellence and maintaining the public’s trust.

To learn more about Raritan Headwaters and its programs, please visit www.raritanheadwaters.org or call 908-234-1852.