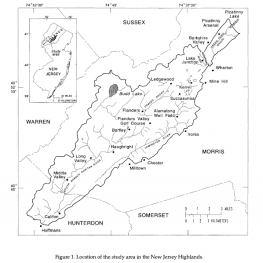

Smack in the middle of the New Jersey Highlands is a long glacial valley that starts at Picatinny Lake in Morris County and stretches south to Califon in Hunterdon County. The valley and drainage basin surrounding it covers nearly 100 square miles. It served as an ice channel for glaciers in the distant past. The Wisconsin glacier was the most recent, but luckily, this one didn’t extend as far south. It stopped a few miles north of Kenvil, where Rt. 46 crosses the flats from Mine Hill to Kingstown Mountain.

Smack in the middle of the New Jersey Highlands is a long glacial valley that starts at Picatinny Lake in Morris County and stretches south to Califon in Hunterdon County. The valley and drainage basin surrounding it covers nearly 100 square miles. It served as an ice channel for glaciers in the distant past. The Wisconsin glacier was the most recent, but luckily, this one didn’t extend as far south. It stopped a few miles north of Kenvil, where Rt. 46 crosses the flats from Mine Hill to Kingstown Mountain.

When the Wisconsin glacier melted, it disgorged massive amounts of water and material collected along its way. The melt-water filled the valley with boulders, rocks, gravel, sand, and silt. Some material got deposited in jumbled conglomerations. Some material settled at different rates as it flowed, generally depositing heavier material first and carrying the lightest material further away. This process created stratified layers of sediment along the valley floor, each with varying degrees of water permeability.

Note: This map and the geological information informing this article are from a 1996 U.S. Geological Survey Water-Resources Investigation Report. https://pubs.usgs.gov/wri/1993/4157/report.pdf

The particulars of deposition are complex, but suffice it to say, the way the outwash filled the valley created what geologists call valley-fill aquifers. These are essentially a series of underground glacier lakes. They are literally under everyone’s feet who lives or works in the valley. This process created the Succasunna plains as well. Today, the valley-fill aquifers below it are primary water sources for thirty-five-thousands residents who rely on the Alamatong and Flanders well fields operated by the Municipal Utilities Authority (MUA) of Morris County. In addition, thousands of more residents and businesses tap directly into the aquifers with private wells.

Imagine this, every drop of rain that falls in the valley’s basin that doesn’t reach the sea or evaporate in the ocean of air flows underground to replenish the water we pump from the aquifers below. The undeveloped land and forests in our valley’s basin are “recharge” areas where the ground is still porous. Plants and trees slow the water flow, giving it time to soak deep into the soil before it evaporates or drains away. Wetlands through which our streams pass also slow the water’s movement allowing time and space for it to seep down and refill the glacier lakes below.

Time and space! Both are essential to capture all the water we need every day. Every parcel of land we develop, every new road or driveway that we pave, and every swampy area that we drain or fill means less water reaching our aquifers. All this speaks only to the volume of water available to us, not its quality. The inescapable truth about our water quality is that everyone who drinks from the valley-fill aquifers will eventually be exposed to most of what we, the basin dwellers, spread on our lawns and roads or discharge into our streams.

(Guest blogger Brian T. Lynch, MSW, is a retired social worker, social service planner and administrative analyst for the state of New Jersey.)