Per – and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a class of synthetic chemicals that have been used in a wide variety of products over the past seventy years. PFAS saw heavy production beginning in the 1940s and can be found in products such as non-stick cookware, paints and varnishes, nail polish, cleaning products, pesticides, and shampoos.[1] PFAS also saw production in the automotive, aerospace, and electronic manufacturing industries as well as waste disposal facilities. While some PFAS have declined in production over the years, their extremely resilient compositions have allowed them to remain in the environment over time.[2] PFAS have earned the name ‘forever chemicals’ due to their unique chemical and physical properties which make many of them extremely persistent and mobile in the natural environment where they now pose a threat to public health.[3]

Per – and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a class of synthetic chemicals that have been used in a wide variety of products over the past seventy years. PFAS saw heavy production beginning in the 1940s and can be found in products such as non-stick cookware, paints and varnishes, nail polish, cleaning products, pesticides, and shampoos.[1] PFAS also saw production in the automotive, aerospace, and electronic manufacturing industries as well as waste disposal facilities. While some PFAS have declined in production over the years, their extremely resilient compositions have allowed them to remain in the environment over time.[2] PFAS have earned the name ‘forever chemicals’ due to their unique chemical and physical properties which make many of them extremely persistent and mobile in the natural environment where they now pose a threat to public health.[3]

When PFAS are indirectly introduced to our drinking water supply, considerable health issues may occur. Some studies have discovered that individuals exposed to PFAS through their drinking water have an increase in serum cholesterol and uric acid levels in the blood. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) exposure has also been associated with an increase in the incidence of kidney and testicular cancer in exposed communities.[4] Although PFAS research is still in development, these risk factors have justifiably caught the attention of both citizens and scientists alike.

Despite these looming outcomes, there is some good news for New Jersey residents. As of February 2021, fifteen states have introduced criteria for drinking water standards and New Jersey has established one of the most protective drinking water standards in the nation for 3 common PFAS- PFNA, PFOS, and PFOA. Public water purveyors must now ensure that water delivered to customers does not contain levels of these chemicals over the new enforceable limits. Smaller water systems servicing schools and some businesses are required to test and treat for PFAS as well. New Jersey has also recently added PFOA, PFOS, and PFNA to the List of Hazardous Substances, which allows the Department of Environmental Protection to exercise additional authority under the Spill Act to respond to a discharge.

Despite these looming outcomes, there is some good news for New Jersey residents. As of February 2021, fifteen states have introduced criteria for drinking water standards and New Jersey has established one of the most protective drinking water standards in the nation for 3 common PFAS- PFNA, PFOS, and PFOA. Public water purveyors must now ensure that water delivered to customers does not contain levels of these chemicals over the new enforceable limits. Smaller water systems servicing schools and some businesses are required to test and treat for PFAS as well. New Jersey has also recently added PFOA, PFOS, and PFNA to the List of Hazardous Substances, which allows the Department of Environmental Protection to exercise additional authority under the Spill Act to respond to a discharge.

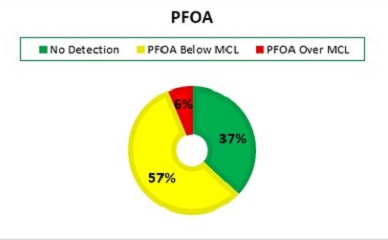

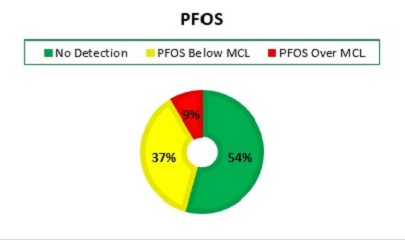

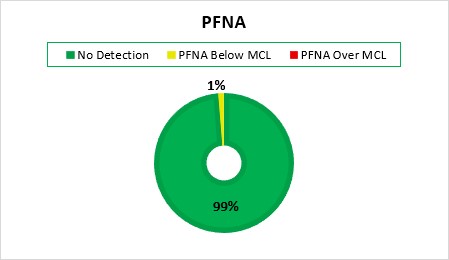

Raritan Headwaters and citizen scientists have joined forces in the effort to research PFAS in New Jersey. Throughout Raritan Headwaters Watershed, citizen science has been at the forefront of collecting data on contaminants. Between March and November, residents and Raritan Headwaters conducted 81 well tests for PFAS inthe following townships: Bethlehem, Branchburg, Chester, Delaware, East Amwell, Franklin, Hillsborough, Kingwood, Lebanon, Raritan, Readington, Tewksbury, and Washington. Of those tested wells, 63% had positive detections for PFAS. Approximately 9.8% of PFOA and approximately 18.9% of PFOS detections were above the New Jersey limit. PFNA was discovered in one well. The highest detection of PFOS is in Readington Township, where a test came back positive showing 950 ppt for PFAS (this is over the MCL by 936 ppt).

By testing your well, you add to the data-campaign for PFAS information across the watershed. As Dr. Robert Laumbach, a professor of public health at Rutgers, explains, “As data accrues from the newly required testing for PFOS, PFOA, and PFNA … we will get a better idea of occurrence across the state and in particular areas.”[5] With more data comes more action. Once enough data is collected, RHA will be able to add PFAS zones to the ‘What’s in Your Water,’ map on our website at raritanheadwaters.org.

By testing your well, you add to the data-campaign for PFAS information across the watershed. As Dr. Robert Laumbach, a professor of public health at Rutgers, explains, “As data accrues from the newly required testing for PFOS, PFOA, and PFNA … we will get a better idea of occurrence across the state and in particular areas.”[5] With more data comes more action. Once enough data is collected, RHA will be able to add PFAS zones to the ‘What’s in Your Water,’ map on our website at raritanheadwaters.org.

Government action for PFAS advisories is in development. At the state level, there is action toward PFAS management. Under the New Jersey Private Well Testing Act, buyers and renters have the right to know the quality of drinking water on the property. This law requires that, prior to closing of the title for a real estate sale, properties with potable wells in New Jersey have untreated groundwater tested for a variety of water quality parameters, including up to 32 human health concerns[6]. In addition to this, landlords are required to test their well water once every five years and must provide each tenant with a copy of the test results. This law now includes a requirement for PFOA, PFOS, and PFNA testing as of December 1, 2021.[7] Additionally, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection recently stated it will look to collaborate with private well owners to install filters that can remove chemicals before they enter a home.[8] Residents who test for PFAS and find that levels exceed the current standards may now apply to the Spill Fund for assistance in installing treatment systems.

At the federal level, The Environmental Protection Agency has discussed a federal Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) for PFOA and PFOS, however this mitigation action is still in the works.[9] However, as of December of 2022, the roadmap strategy by the EPA has several key components missing from their roadmap to address PFAS. For example, there is no current mention of ending approval of new PFAS chemical usage, regulating emissions of PFAS into air, and regulating discharge of PFAS into the water from all industrial sources.[10] As of April of 2022, Maine became the first state to fully ban the use of biosolids that contain PFAS in land applications… Perhaps New Jersey will follow suit after ample research has been completed. As it currently stands, it is up to citizen science and grass-roots organizations to test the local wells to set the precedent and need for support for decreasing PFAS in our drinking water.

At the federal level, The Environmental Protection Agency has discussed a federal Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) for PFOA and PFOS, however this mitigation action is still in the works.[9] However, as of December of 2022, the roadmap strategy by the EPA has several key components missing from their roadmap to address PFAS. For example, there is no current mention of ending approval of new PFAS chemical usage, regulating emissions of PFAS into air, and regulating discharge of PFAS into the water from all industrial sources.[10] As of April of 2022, Maine became the first state to fully ban the use of biosolids that contain PFAS in land applications… Perhaps New Jersey will follow suit after ample research has been completed. As it currently stands, it is up to citizen science and grass-roots organizations to test the local wells to set the precedent and need for support for decreasing PFAS in our drinking water.

If you test for PFAS in your well and find a considerable amount present, we recommend several water treatments options for private wells. Water filtration units that use granulated activated carbon (GAC, also called charcoal filters) and reverse osmosis (RO) can be effective in removing PFAS chemicals from drinking water.[11] With more testing and data collection, we expect to have more explicit recommendations for treatment. In the meantime, it never hurts to test your water for contaminants. To learn more about well testing, visit our website at https://www.raritanheadwaters.org/get-involved-2/groundwater-well-testing/.

—————————————————–

[1] Raritan Headwaters, “Spills, Floods, and ‘Forever Chemicals’: Responding to Concerns Over Drinking Water Safety,” (September 27, 2022), 17. https://www.raritanheadwaters.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/WTLL-9.27.22-Drinking-Water_PFAS-Presentation.pdf.

[2] Avram J. Frankel, “PFAS Background,” in On Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: Suggested Resources and Considerations for Groundwater Professionals, Vol 59, 4 Groundwater (The Groundwater Association, April 3, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1111/gwat.13101.

[3] Raritan Headwaters, 17.

[4] New Jersey Department of Health, “Health effects of PFAS,” in “Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Drinking Water,” Environmental and Occupational Health Surveillance Program (November, 2021). https://www.nj.gov/health/ceohs/documents/pfas_drinking%20water.pdf.

[5] Jon Hurdle, Half of wells tested exceed limits for ‘forever chemicals,’ Energy & Environment, Water. NJ Spotlight News. (March 28, 2022). https://www.njspotlightnews.org/2022/03/pfas-forever-chemicals-widespread-private-water-wells-pfna-pfoa-pfos-nj-dep/

[6] New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, “PFAS in Drinking Water,” accessed December 28, 2022. https://www.nj.gov/dep/pfas/drinking-water.html.

[7] New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection: Division of Water Supply and Geoscience, “Private Well Testing Act (PWTA), accessed December 28, 2022. https://www.state.nj.us/dep/watersupply/pw_pwta.html.

[8] Jon Hurdle, Half of wells tested exceed limits for ‘forever chemicals.’

[9] United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2020a. PFOA, PFOS and other PFASs. EPA’s PFAS action plan (updated February 28, 2020). https://www.epa.gov/pfas/epas-pfas-action-plan

[10] “Inside EPA’s Roadmap on Regulating PFAS: Toxic “forever chemicals” remain laxly regulated,” Earthjustice, (December 12, 2022), accessed December 28, 2022. https://earthjustice.org/features/pfas-chemicals-epa-roadmap.

[11] New York State Department of Health, “Water Treatment Options for Private Wells,” in PFAS in Private Wells, (New York Center for Environmental Health, December, 2021) accessed December 28, 2022. https://www.health.ny.gov/environmental/water/drinking/docs/pfasandprivatewells.pdf.